Throughout the Islamic Republic's periods of mass opposition, such as 2009, 2019, and 2022, the one thing lacking in protest movements was a unifying and coordinating figure.

If the Islamic Republic fears mass protest movements in general, the idea of a unifying political figure who can turn dispersed rage into coordinated action and a plausible alternative is something the regime cannot tolerate.

That unifying figure is Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi, the son of the late, deposed Shah, who has called for protests and coordinated movements on the ground within Iran, and whose name is called by millions of people on the streets when they shout “Pahlavi barmigardeh” (Pahlavi will return) and “Javid Shah” (long live the Shah).

“In late December and early January, the Iranian people had already bravely taken to the streets as they have so many times before,” Pahlavi told The Jerusalem Post last week. “They called on me for leadership and for direction. The regime was weaker than ever, the people more united than ever, and so I called for coordinated action on January 8 and 9, and millions took to the streets.

“My position has been consistent for over four decades: Iran’s future will be decided by the Iranian people themselves,” he said. “They are the boots on the ground needed to end this regime.”

The regime is now three weeks into an internet shutdown to prevent communications on the ground, leaving Iranians trapped, unable to communicate with the outside world. There are also reports of massacres taking place, with the official death toll just under 7,000, but the truth is much higher. Estimates of January 8-9, when the regime indiscriminately opened fire on protesters, read 40,000-plus killed in those two days alone.

Pahlavi has already signaled that he is preparing to return to Iran. “My team and I are actively making the necessary preparations for my return,” he told the Post. “I am prepared to do this even before this regime falls to be alongside my compatriots for the final battle.”

As the sole unifying voice among the Iranian opposition and a symbol of the monarchy that preceded the 1979 revolution, Pahlavi has the regime nervous enough to target him.

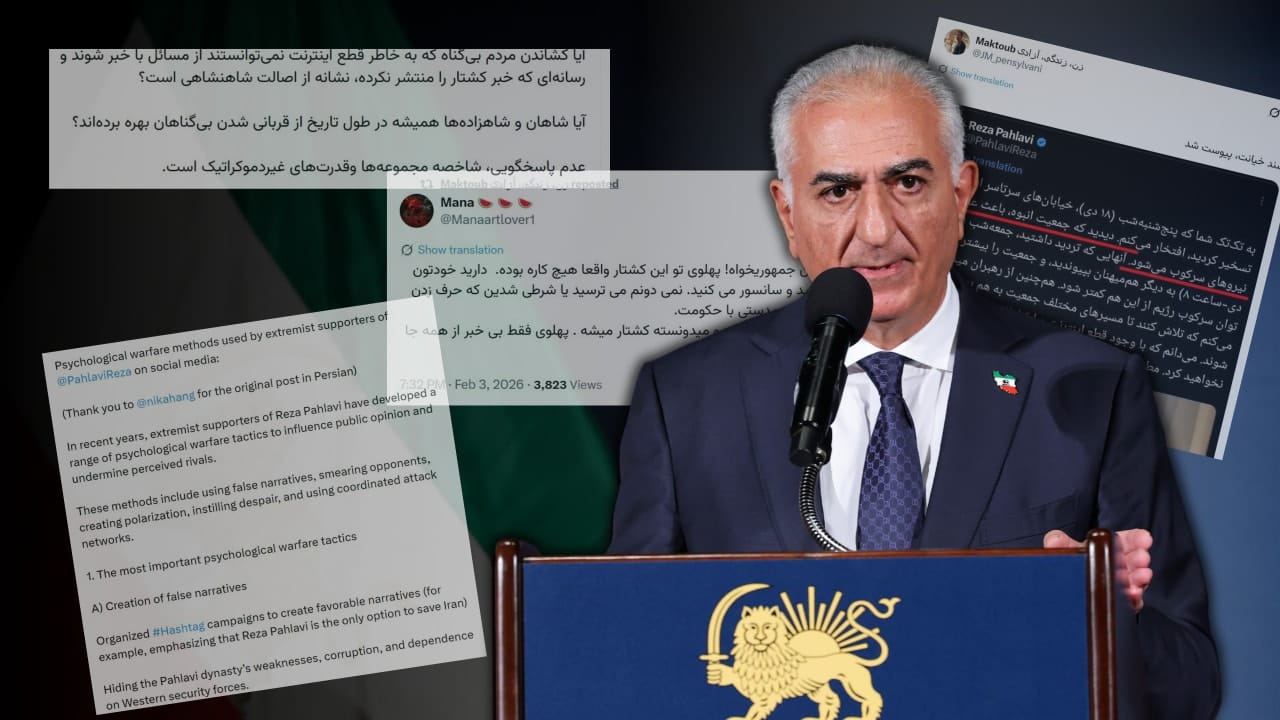

Saeed Ghasseminejad, an Iranian economist and senior adviser on financial economics at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, plus a member of the prince’s inner circle, told the Post this week there were reports that Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei “issued a directive” to mobilize the cyber apparatus against Pahlavi, with a specific narrative line: “that Prince Reza Pahlavi is responsible for the deaths of the protesters.”

“It is something you hear from Western journalists too,” he added, arguing that regime narratives are echoed both by sympathetic reporters and through more hostile means.

A leaked internal memo from Tasnim News Agency’s Strategic Center - one of the main media networks inside Iran - and reported by Iran International, offers a rare look at how an IRGC-linked media ecosystem tries to shape perceptions of the uprising, and how it tries to neutralize Pahlavi as a political alternative.

According to the memo, the objective is to guide audiences toward viewing Pahlavi not as a credible domestic leader but as a Western-backed media instrument, all the while framing the uprising as foreign-driven by the CIA and Mossad rather than rooted in public anger at the Islamic Republic.

The document outlines three main lines.

First, it denies that Pahlavi has a meaningful social base inside Iran, claiming protests were planned “on the ground” by the United States and Israel, and portraying his statements as media coverage rather than leadership.

Second, it seeks to distinguish broad social anger from support for Pahlavi, arguing that many protesters expressed accumulated frustration with the Islamic Republic rather than endorsing his political “qualifications.” Even supportive slogans are reframed as more a rejection of the system rather than approval of him.

Third, it focuses on degrading his credibility — portraying him as inconsistent, unwilling to take responsibility, lacking courage, and ultimately as a “puppet,” rather than a serious political actor.

The memo acknowledges Iranians’ dissatisfaction with the ruling clerics, but tries to frame the prince as an unsuitable alternative.

The memo explains the message. But Tehran’s ability to push a line depends on who can speak during crisis periods and how quickly aligned messaging can move. That depends on how deeply-connected you are within the regime.

KHOSRO ISFAHANI, a senior analyst with the National Union for Democracy in Iran, described a model that took shape after the 2009 protests - the regime clamps down on the broader public online, but protects access for selected circles whose role is to maintain the state’s message at key moments.

“This started around 2009, when the regime began clamping down on online freedoms,” Isfahani told the Post. “At the same time, they saw the negative impact on their own operations — and on the day-to-day lives of citizens and businesses. So they began granting this kind of access to selected groups: businesses, academic centers, and influencers aligned with the regime.”

Through what are known as “white SIM cards,” the regime can “select a group, give them unfiltered internet, and give them more latitude in what they can say on social media,” he said. “But if you’re part of one of these incubators or circles, you can have more freedom — as long as, at critical moments, you echo the exact message coming from the regime.”

Isfahani explained this is how “narrative control” becomes operational inside the Islamic Republic.

The analyst also explained how the regime’s online messaging frequently behaves like a synchronized system, both from fear of punishment and the promise of reward for collaborators. He pointed to the response after Iran shot down Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752 in January 2020 en route from Tehran to Kyiv.

“When they downed the Ukrainian airliner, regime insiders all pushed the same line: ‘This is probably an accident. Airbus planes are bad etc,’” he stated, “denying the evidence until the IRGC itself came out and accepted responsibility.”

Similar patterns appeared during the 2019 protests, when the regime stooges “pushed the line that: we don’t have enough resources to subsidize fuel, so the regime had to cut subsidies,” Isfahani told the Post.

“The same talking points that the Islamic Republic’s lobby in the West repeats on TV get pushed through social media as well,” he added. “These individuals get recycled and used by foreign journalists, including journalists with Iranian heritage.”

He described the regime’s framing of the current unrest as unfolding in phases and explained that the shift becomes more visible as the opposition begins to unify.

“In the first week, the regime tried to frame this as legitimate protests over economic issues,” he said. “These influence networks echoed that: blame the government for economic failings, demand that the government find solutions. The same message was coming from the parliament speaker. The government itself was pushing that line.”

The breaking point for Tehran came when the crown prince took on the mantle of coordinating protests.

“Immediately after the Crown Prince issued his call, and we saw that massive outpouring of the population who have determined that the Islamic Republic, in its entirety, has to go — the language these influence networks used changed immediately,” Isfahani said.

This mirrors the logic of the Tasnim memo by allowing some form of dissent but blocking any form of an acceptable alternative from appearing.

The regime has already shown in the past that it can weaken a unifying online symbol.

Iranians used the hashtag #MahsaAmini across social media for millions of posts during the 2022 protests after Amini’s death in state custody, turning X into a central arena for dissent. Within months, activists and researchers documented a familiar response from the regime, including shutdowns and surveillance, combined with coordinated pro-regime activity and disinformation, which began to flood the online space with noise and confusion, thereby breaking apart the opposition.

Bots on the ground

State narrative through stooges is one layer. Amplification on a large scale is another, and it helps explain how a line can appear everywhere at once.

Open-source research by Golden Owl described a hierarchical influence system on X built around “originators” producing narratives and “amplifiers” pushing them out to the public. Golden Owl reported analyzing 7,924 account records across two datasets, resulting in 7,515 unique accounts after deduplication, and identifying 510 originator accounts and 2,503 amplifier accounts.

Its content analysis listed “Anti-Pahlavi Campaigns” as a recurring category, describing sustained efforts to target the Pahlavi name and constitutional monarchy advocates through delegitimization and repeated attempts to associate them with foreign enemies.

Golden Owl also flagged bot-like and inauthentic behavior indicators across the network, reporting that more than 40% of accounts exhibited at least one such marker — including empty or minimal biographies, default profiles, numeric username patterns, extreme posting rates, and mass-following behavior. The researchers stressed this does not prove all such accounts are fully automated; some may involve human operators running multiple accounts or semi-automated workflows.

Isfahani said he has seen a commercial market for this activity within Iran, but argued the more effective operations are tied to state actors.

“Back in 2018–19, I identified a bot farm,” he told the Post. “I actually found an ad for it If you want reformers, we have them. We have hardliners. We have monarchists. We have opposition figures. We have communists. They were treating it like a business, just selling it. They didn’t care about politics. It was simply about money.”

But, he added, “These aren’t random people. These are operatives.” The larger, more effective ones, he said, come out of the Intelligence Ministry, which he described as specializing in “narrative-building — fake news, distortion of facts and social engineering.”

The result is a message from state actors that within minutes can be reproduced or supported across the globe, something the Post investigated in December when a Khamenei speech on austerity received almost identical replies within minutes of the speech.

For Tehran, targeting Pahlavi is less about the man than about the threat he poses to the regime. Protests, which in the past have repeatedly lacked leadership, have finally coalesced around a figure who can coordinate the street, represent Iran on the world stage, and offer an alternative to the Islamic Republic.