In the Palestinian narrative, the events of 1947-1949 are referred to as the Nakba – “catastrophe” – in which some 750,000 Arabs fled or were driven from their homes. But the Palestinian disaster as dispossessed, stateless refugees precedes the founding of Israel by more than two decades and can be blamed on Perfidious Albion (aka the UK) rather than the Jewish state.

A century ago, Great Britain enacted the Palestine Citizenship Order-in-Council, granting passports to the residents of the territory of the British Mandate. The law, which came into force on August 1, 1925, had the unintended effect of denying citizenship and travel documents to some 20,000 to 30,000 Arabs born in Turkish-ruled Palestine who were living abroad. In the 2016 book The Invention of Palestinian Citizenship, 1918-1947, historian Lauren Banko explains how these Arabs came to be caught in this Kafkaesque bureaucratic nightmare. She begins with the Ottoman Nationality Law of 1869, which was meant to do away with the millet system [whereby religious communities had some autonomy in managing their internal affairs] in favor of secular nationality.

Citizenship of that vast empire was voided at the end of World War I when Ottoman Turkey collapsed. While residents of Anatolia received new [citizenship] papers following the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in Ankara on October 29, 1923, the empire’s former subjects now living in the League of Nations’ Middle East mandates of Palestine, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon were excluded.

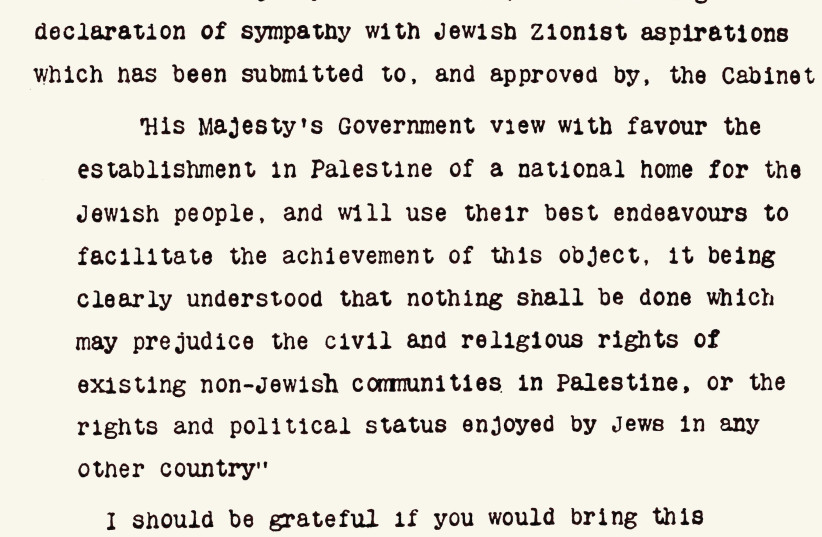

The mandatory powers Britain and France, both appointed as international trustees, wrestled with the status of their new subjects. The status of those mandates as trusteeships rather than outright colonies or protectorates had little precedence. Banko explores how Britain drew upon its imperial experience in the governing of “Oriental races” and “subject races” in Egypt and India. The League of Nations obligated Britain to enact a law for the acquisition of Palestinian nationality for Jewish immigrants, as framed by the 1917 Balfour Declaration. But the league’s demand also encompassed the Arab population, since the mandate stipulated that the Jewish national home policy not prejudice the civil or religious rights of the existing population.

In 1922, Mandate Palestine’s first attorney-general, a British Jew named Norman Bentwich, drafted legislation submitted to the Colonial Office in London. His proposed law envisioned an apolitical quasi-colonial citizenship granting limited civil and political rights. Indeed, Britain never established a legislative council in Palestine as called for by the League of Nations; however, the 1922 Palestine Electoral Order-in-Council was established, which set the regulations for elections for the future parliament in Jerusalem.

Bentwich incorporated elements of Ottoman nationality legislation. As well, he drew upon the empire’s experience of colonial citizenship. Some of this inspiration came from Lord Cromer in Egypt, who served as Britain’s consul-general in Egypt from 1883 to 1907. His rule featured procedures designed to separate Europeans from local natives, such as the tiered Mixed Courts.

In the case of Palestine, and in keeping with Britain’s divide and rule policy, the procedures to acquire citizenship separated Jewish immigrants from the local Arab population.

Efforts bearing fruit

Bentwich’s efforts bore fruit in the 1925 Palestine Citizenship Order-in-Council, signed by King George V, and implemented in the Palestine Mandate as the first piece of legislation to recognize Palestine’s Arab community as citizens rather than “ex-enemy Ottoman subjects.” Like all the other imperial decrees, it was enacted by London, not by the Government of Palestine. More than 70,000 brown-covered passports were issued, marked in English “BRITISH PASSPORT,” followed by “PALESTINE.” The documents, signed by the high commissioner, ceased to be valid on the termination of the Mandate on May 15, 1948.

On the last page of the passport, it was noted: “Applications for the issue or renewal of Palestine passports by residents in Palestine should be made on the appropriate form at one of the offices of the Department of Immigration. Residents abroad should make application to British diplomatic or consular officers; in the case of residents in the United Kingdom, the British Dominions, Colonies and Mandated Territories, to the local authorities”

Banko writes, “It is interesting to note that until the middle of 1924, the order-in-council draft to regulate Palestinian citizenship was titled the Palestinian Nationality Order-in-Council. Only in May did colonial officials recommend this be changed to the Palestinian Citizenship Order-in-Council to avoid complications. By July, the draft order had ‘nationality’ crossed out and replaced with ‘citizenship.’ Only shortly before the order passed, the Colonial Office changed ‘subject’ to ‘citizen’ in all places and made a note that ‘national’ in the Treaty of Lausanne meant both subject and citizen in the Citizenship Order.”

Clause Twelve of the Palestine Citizenship Order-in-Council specified that former Ottoman subjects usually residing in Palestine who were absent on the date of its ratification would become citizens if they returned to Palestine within 24 months and assumed permanent residence.

British diplomats made some effort to publicize this crucial clause to émigrés living in Egypt, Honduras, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, and Europe; but in an era before mass communication, many of those born in Ottoman Palestine and living abroad were unaware of the new citizenship regulation. In any case, in order to qualify, the law required that they leave their homes abroad and return to the Mandate. Those former Turkish citizens who had left and missed the two-year window would have to undergo naturalization to become citizens.

Many Palestinian Arabs saw this as unjust, since newly arrived Jewish immigrants faced no such requirement. They argued that the order-in-council was illegal, as it was not enacted by a parliament elected by the people.

When one considers that every exile had kinsmen in Palestine, the discriminatory law affected the majority of the population. Even fellahin [peasants] who never traveled abroad, and thus never acquired a passport, were united in their opposition to Britain’s citizenship act. By 1948, only 500 of those native sons denied citizenship had managed to return.

Banko writes, “The Palestinian Arab Executive leadership unanimously rejected the citizenship legislation on the basis that it denied citizenship to native-born Palestinians while privileging Jewish immigrants, and that it neglected provisions for natural civil and political rights. The press, especially Issa Bandak’s Jerusalem newspaper Sawt al-Sha’b, became the main medium through which discussions on the citizenship order and letters from the Diaspora were published. In periodicals as well as in protest memorandum, Palestinians referred to the order as the ‘nationality law’ and generally used the Arabic term for ‘nationality’ (jinsiyya) in reference to the more legalistic and perhaps modern ‘citizenship’ (muwatina). Popular leaders and newspaper editors wrote to the British and League to decry the denial of citizenship to thousands of Palestinians who emigrated or lived abroad.”

In 1926, Bandak established the Committee for the Defense of Palestinian Arab Emigrant Citizenship Rights, which lobbied tirelessly into the 1930s against the citizenship order and its amendments. Bandak, who repeatedly served as mayor of Bethlehem and as a Jordanian diplomat, was unable to return to Palestine after the 1967 Six Day War and died in Santiago, Chile, where some 500,000 Palestinians today live.

Rounding out the historical perspective, Banko notes that Arabs spoke of “the right of return” already in the 1920s. The huge grievance over disenfranchised native-born Palestinians fed into the Arab Revolt of 1936. While the Peel Commission report of 1937 mentioned the plight of the stateless Palestinians, nothing was done to correct the injustice.

Banko’s book about the stateless Palestinians of the 1920s gives context to the 750,000 Arabs who became refugees from Mandate Palestine in 1948, to the 250,000 driven out of Kuwait in 1991, and to the two million stripped of their Jordanian passports by King Hussein and his son Abdullah II.■