This coming Saturday, November 22, will mark 62 years since an assassin’s bullet ended the life of John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, as his motorcade was traveling through the streets of Dallas, Texas.

For those who were alive at the time, it is one of those dates, like 9/11 or, more recently, October 7, that stays in one’s memory bank forever. And, of course, we will always be able to recall where we were when we heard the news.

That fateful Friday, I was working as an active-duty signal officer serving in the US Army Reserve assigned to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Lewis Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio. At one point in the early afternoon, the word got out that the president had been shot at 12:30 p.m. central time and was pronounced dead 30 minutes later.

Witnessing history

Disbelief was in everyone’s eyes, as it had been 61 years since William McKinley was assassinated, the last president to have been murdered while in office, which was well before those of us working at NASA were alive.

Ninety-eight minutes after Kennedy was pronounced dead, as the US Constitution provides, then vice-president Lyndon Johnson was sworn in as the 36th president in a hastily arranged ceremony on Air Force One presided over by a federal judge, Sarah T. Hughes.

Sid Davis, a Jewish native of Youngstown, Ohio, who died on October 13 of this year at the age of 97, was a White House correspondent for Westinghouse Broadcasting and one of three reporters who witnessed the swearing-in ceremony.

He was on the press bus in the presidential motorcade in Dallas that day, and from the moment that three rifle shots cracked across Dealey Plaza and the fatally wounded president slumped forward in his open limousine, Davis recently recalled, chaos reigned, as Secret Service agents scrambled, crowds panicked, and reporters were trapped in traffic jams.

According to records of that day, as the limousine sped to Parkland Memorial Hospital, the press bus drove to the Trade Mart where Kennedy had been scheduled to speak. Davis got a ride to the hospital, where he saw the bloody limousine, interviewed the priest who gave Kennedy the last rites of his church and phoned in a series of reports on the president’s death.

A White House official then picked Davis, as well as Merriman Smith of United Press International and Charles Roberts of Newsweek magazine, to witness the transfer of power to Johnson. The newsmen were sped to Love Field, where Air Force One was waiting. Johnson, his staff, and his wife, Lady Bird, were already on board, as was Jacqueline Kennedy, the widow of the slain president.

Mrs. Kennedy was in the rear of the plane with the recently loaded casket of the dead president when Johnson invited her to join him up front for the swearing in, to which she agreed.

Davis, in his memoirs, described her as “sad, calm, her eyes wide but questioning,” adding that “there were blood stains and pieces of flesh on her two-piece raspberry suit, congealed blood on her stockings, and blood on her right wrist.” She had held her husband’s shattered head in her lap, he noted, and the bleeding had been profuse.

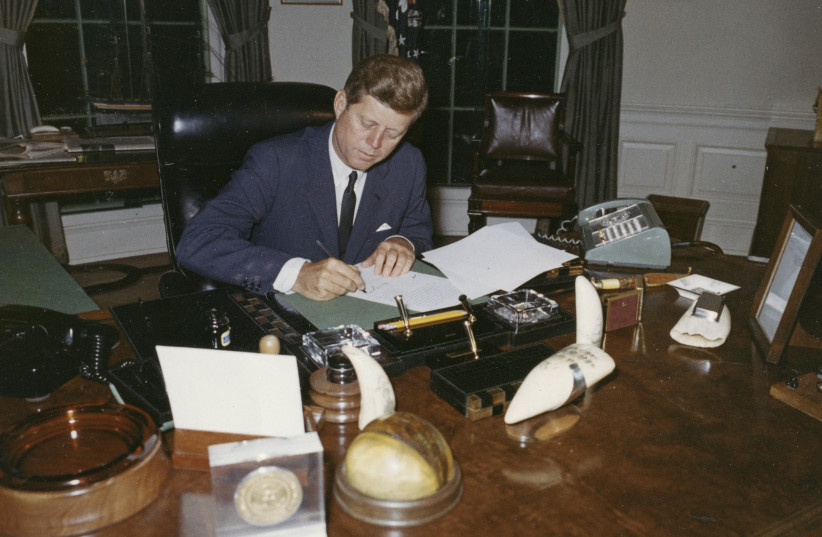

John F. Kennedy was a strong supporter of a young Israel, though the relationship was complex, as they always seem to be, even today. As president, he supported Israel by providing military aid such as 1962’s sale of Hawk missiles, maintained good relations with Jewish leaders both in the US and Israel, and tripled the financial assistance provided to us at the time as well as a much-needed line of credit.

Nevertheless, he also pressured Israel on its nuclear program and sought a diplomatic solution with both Israel and Arab nations.

In his public statements he called Israel “the child of hope and the home of the brave” and supported our right to exist and our security concerns as well.

In his memory the Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael-Jewish National Fund created a fitting memorial in the hills of Jerusalem known as Yad Kennedy in Hebrew. The 28-meter-high memorial is shaped like the stump of a felled tree, symbolizing a life cut short.

Inside is a bronze relief of Kennedy, with an eternal flame burning at the center. It is encircled by 51 concrete columns, one for each of the 50 states plus one for Washington, DC, the US capital. The monument was built in 1966 with funds donated by American Jewish communities.

A wave of assassinations

Sadly, the 61-year hiatus from presidential or high-level political assassinations prior to Kennedy’s death seems to have ended in 1963. Just five years later, in 1968, Kennedy’s brother, Robert Kennedy, was also killed by an assassin’s bullet after a hotel rally in Los Angeles.

That same year, civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., was gunned down while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. In 1986 there was an attempted assassination of then-president Ronald Reagan on a street in Washington, while last year President Donald Trump was targeted by an assassin in Pennsylvania while campaigning there.

Another potential assassin was later discovered on property adjacent to the president’s home in Florida.

To many of us who were living in the US at the time, Kennedy will always be known for staring down the Russians during the Cuban Missile Crisis and getting them to “blink” first. The 12 days from October 16 to 28, 1962, were probably as close as the world has ever come to full-scale nuclear war.

As importantly, he did it with grace, composure, and the projection of self-confidence, all aspects of presidential conduct that could serve as a lesson for today’s politicians. In his 1961 inaugural address, he famously urged Americans to “ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.” An inspirational message that is as meaningful today as it was 62 years ago. May his memory be blessed.

The writer, an international business development consultant, has lived in Israel for 42 years, is a former national president of the Association of Americans and Canadians in Israel, a past chairperson of the board of the Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies, and chair of the Executive Committee of Congregation Ohel Nechama in Jerusalem.