Since 1979, the Egypt-Israel peace treaty has been a cornerstone of US strategy in the Middle East, ensuring regional stability, projecting American influence, countering adversaries, and advancing national security interests. While the bilateral relationship has endured periods of tension, the resulting “cold peace” has largely held because Washington acted as its guarantor.

Today, however, that cold peace is visibly fraying. Weapons smuggling across the Sinai-Israeli border, an Egyptian military buildup in Sinai in violation of the treaty, and rising public hostility toward Israel, exacerbated by the two-year war in Gaza, threaten to unravel the agreement, posing strategic risks not only to Jerusalem but also to Washington.

Reports from the ground underscore the urgency: Ynet describes “an aerial convoy of dozens of drones” smuggling weapons into Israel, while Axios journalist Barak Ravid notes that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has asked Washington to intervene against Egypt’s military buildup, with US-led observation overflights sharply reduced.

For Washington, the path forward is clear: reinforce treaty obligations, maintain strategic oversight, and guide both Cairo and Jerusalem to adapt their security posture to evolving threats while preserving Camp David as a cornerstone of regional stability and American influence.

Egypt-Israel tensions remain after the treaty

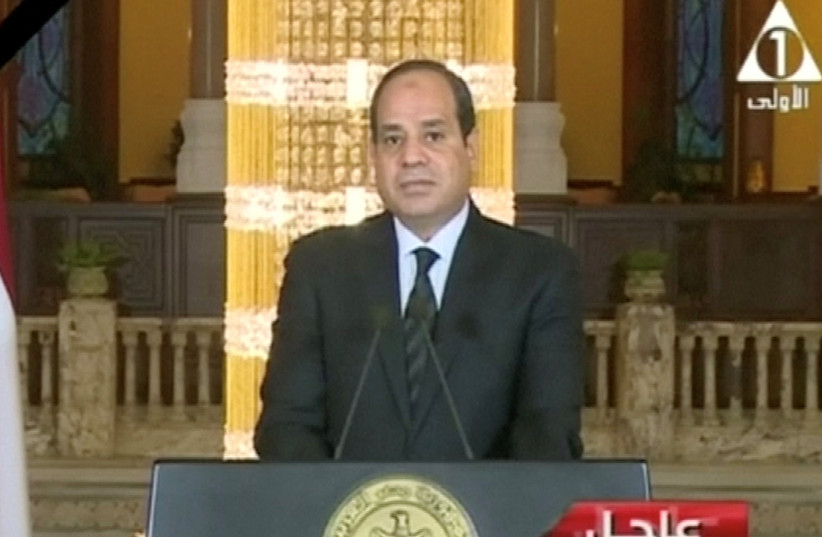

While the treaty ended direct conflict, it never produced genuine reconciliation. Egyptians rarely travel to Israel, and state-controlled media, mosques, and schools frequently portray Israel in hostile or antisemitic terms, fostering skepticism and outright hostility. The 2011 Arab Spring revealed the fragility of Egypt’s internal consensus: Free elections brought the Muslim Brotherhood to power, only to be overturned by the Sisi-led military.

Islamist sentiment remains strong, and many Egyptians sympathize with Gazans, seeing Hamas as a symbol of resistance against what they perceive as illegitimate Jewish dominance in the Levant. These attitudes complicate Cairo’s ability to maintain even a cold peace.

The Camp David framework envisioned the eastern Sinai as a demilitarized zone, preventing Egypt from massing troops as it did in 1956, 1967, and 1973. Egypt’s current deployments of tanks, troops, tunnel networks, and upgraded airfields raise questions about its long-term intentions toward Israel.

For Jerusalem, these deployments risk creating a new military front. From Cairo’s perspective, Israel has historically been its primary military concern, reflected in decades of tactical planning and war games. From Washington’s standpoint, these developments challenge the sustainability of a peace accord that the United States helped forge and continues to underwrite.

Egypt’s military actions in Sinai are driven primarily by domestic security concerns rather than an Israeli threat. Cairo is determined to prevent a mass influx of Palestinians from Gaza, fearing destabilization. Unlike Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan, which absorbed millions of Syrian refugees during the civil war, Egypt has tightly sealed its border, drawing little criticism for its hardline stance.

This reluctance stems from the essence of Hamas, an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood, which Sisi views as his primary domestic adversary. Suppressing the Brotherhood and keeping Islamist Gazans out of Egyptian territory serve both security and political objectives, while Cairo maintains the appearance of defending Palestinian interests.

WASHINGTON, UNDER both the Biden and Trump administrations, has largely refrained from leveraging America’s diplomatic and economic influence to encourage Egypt to play a constructive role by accepting Gazans. By not combining incentives with pressure, the US has missed opportunities to relieve the Gaza humanitarian situation, bolster regional stability, and allow Israel to degrade Hamas’s operational capabilities with the civilian human shields moved out of harm’s way.

The United States provides Egypt with roughly $1.3 billion annually in military assistance, making Cairo the second-largest recipient of US aid after Israel. With Sisi framing Israel as an “enemy” and violating treaty obligations, Congress has questioned whether this support remains justified.

Paradoxically, Israel supporters in Congress, as well as Israeli politicians and military officials, have historically defended Egypt against aid reductions. While Cairo faces significant security challenges in Sinai, including ISIS and Bedouin smugglers, its military buildup increasingly targets Israel, raising questions about its ultimate goals.

Sisi has strained Egypt’s relationship with America by giving sanctuary to Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad members in Cairo while strengthening ties with America’s strategic competitors, including Russia and China. US policymakers also face Egypt’s troubling human rights record: tens of thousands of political prisoners, mistreatment of Egypt’s Coptic Christians, restrictions on media and dissent, and a military-dominated economy that leaves ordinary Egyptians impoverished.

While supporting authoritarian partners is not new in US Middle East policy, continued military aid becomes harder to justify when it diverges from advancing American security interests.

Washington should recalibrate its approach toward Cairo. Sisi must receive clear, private warnings that American aid will not continue without tangible steps to de-escalate tensions, end anti-Jewish incitement, and engage constructively with Israel.

Egypt should recommit to the letter and spirit of the 1979 peace agreement and stop military buildups in Sinai that violate the treaty. Targeted incentives can encourage Egypt to accept Gazans on its side of the border, while incremental human rights improvements, such as releasing political prisoners and opening space for civil society, should also be pursued.

Conditioning portions of military aid on Egypt’s de-escalation with Israel and constructive engagement on Gaza would provide Washington with leverage without destabilizing the relationship. Should Egypt refuse to cooperate, US assistance could be redirected toward economic development programs that reach Egyptians directly, reducing the military’s monopoly on aid.

In conclusion, Egypt’s current trajectory poses serious risks to regional stability, US interests, and Israel’s security. Weapons smuggling, a growing military presence in Sinai, overt hostility toward Israel, and closer ties to Islamist groups signal a dangerous drift. The 1979 peace agreement, once a linchpin of US strategy, is under increasing strain.

The American goal must be to reimagine the trilateral relationship between Israel, Egypt, and the US, ensuring compliance with Camp David while fostering meaningful reconciliation. With 2026 approaching, the “cold peace” risks fraying further, a scenario neither the US nor Israel can afford to ignore. Washington must act decisively to preserve the Camp David Accords before they unravel.

The writer is the director of MEPIN, the Middle East Political Information Network, and the senior security editor of The Jerusalem Report. He regularly briefs members of Congress, their foreign policy aides, and the State Department.